Take a moment and picture yourself teaching. What comes to mind? Is it a favorite instructional activity, a student’s inspiring essay, or a moment when a student shared something insightful about their lives? Whatever it is, I am sure it stirred up many emotions and memories that you may or may not want to remember. Now I invite you to do the same exercise, but this time, please visualize the invisible teaching you do each day. No one can directly see these actions, yet they are as valuable to student learning as any observable practice. Are you still not sure what I mean?

Invisible teaching practices include the feeling you have of sincere curiosity about your students or the deep sense of support you hold when you notice a student struggling. Even the empathetic mindset you use to plan a lesson or the facial expression you give to a student to show that they matter to you are examples of invisible teaching practices. In my perspective, most of our value as educators comes from these invisible actions, we perform each day with students. Although there is an endless list of invisible work that you can and should do with our students, I want to share a few invisible teaching practices that I found helpful in building community and helping my students succeed in my classroom.

Treat Students as Subjects, Not Objects

In their book, Everybody Matters, Bob Chapman and Raj Sisodia write, “the majority of employees in the United States go home every day feeling that they work for an organization that doesn’t listen to or care about them but instead sees them nearly as functions or objects as a means to the success of the organization” (Pg. 69). Our schools are no different. More often than not, educational institutions’ practices and policies recognize students as objects of a lesson or an outcome of a teacher’s effort rather than a subject responsible for their learning (Freire 1996). In my view, our current educational system operates from the perspective of “knowing is repeating something in authority figure told them” (Felton & Lambert 2020, Pg. 92).

From my perspective, students often view school as a series of transactions of mechanical sense of knowledge and rote skill development and less about learning how to ask more critical questions. When a school treats its students as mere objects, there can be detrimental effects. For one, schools reduce their practices to transactions and evaluation, leaving students to perceive that their teachers don’t value them as individuals but instead see themselves as valuable only when they mimic their teacher’s expertise. Sadly, we teach simple transactions where a student gives the teacher their work in exchange for points or technical feedback due to lack of resources or time. This reductive practice can make students see education as a sterile process of hoop-jumping devoid of meaning or purpose. In other words, they see school only as a game with specific rules to follow.

How Can You Treat Students as Subjects and Not Objects?

In their book Relationship Rich Education: How Human Connections Drive Success in College, authors Felton and Lambert write that “taking time to ask students what their story is and using the resulting information as a departure point for teaching can create more student-centered classrooms and more reciprocal relationships based on mutual trust” (Pg. 3). When you ask students about their lived experiences, your teaching practice can lead to more authentic and sincere relationships with your students and potentially gain more context about who they are and their learning needs. Even a question such as, “Interesting, what makes you say that?” can make students feel like you value their thinking, experience, and individuality.

Relational teachers, teachers who value their students as learning subjects, see the time with their students as an opportunity to cultivate one of the most basic human needs: belonging. These teachers help students recognize that their thoughts matter and respect and care for each student regardless of their level of proficiency. In a 2014 Gallup Purdue poll of college graduate students, researchers found that if an employed graduate noted they had a teacher who cared about them as a person, they reported higher levels of workplace engagement and a sense of thriving in their well-being.

Further relational teachers see teaching first and foremost as a conversation with students. To teach our students effectively, we should know what they know, what they care about, who they are now, and who they are becoming (Schlosser 2014). Taking time to initiate interaction and listen to what the students are trying to say about themselves while you teach is essential in being more relational in your practice and understanding your students.

Measure the Strength of Relationships in Your Classroom

Whether intentional or not, many educators continue to reduce the perception of the effectiveness of a school to its measurable outputs such as grade distributions, graduation rates, and exam scores. Schools are rated and measured on these metrics. Yet, these same ranking systems exclude measures of connections, the strength of communal bonds, and levels of collective school efficacy since they are difficult to measure. The absence of these critical metrics leaves schools to ignore this valuable phenomenon when evaluating teacher performance and school culture.

Thinking back about my career as a student, my teachers and professors did not measure the strength of relationships, only technical knowledge. They never seemed to care what I felt about the class and their teaching, whether I felt like I belonged or that my feelings mattered. This perspective made me value earning points and grades over building supportive relationships, as well as value being an individual over being a part of a learning community. When schools don’t value and continually measure the strength of the relationships in their classrooms, they may deny students the chance to develop a complete sense of self.

How Can You Measure the Strength of Relationships in Your Classroom?

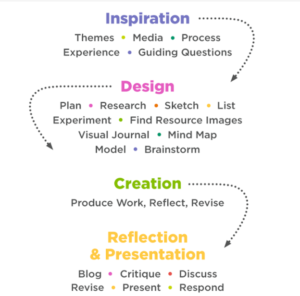

Once you begin to measure the impact of your relational practices, you are more likely to develop more meaningful relationships with your students that transform their educational trajectories (Espinoza, 2011); as we can measure, we can more easily change. Working within classrooms that prioritize student-to-student relationships may better help students believe in their inherent learning capacity. At my school, where I am assistant principal, we ask our teachers of introductory courses at my high school to emphasize and measure the impact of relationship building, track their instances of peer-to-peer mentoring, and develop active learning pedagogy. (Felton & Lambert, 2020).

We also ask our teachers to use assessment as a vehicle to measure the relationship quality with their classrooms. Our teachers use assessment not solely to evaluate students but also as an opportunity to get to know their students. We call this process: dialogic assessment, and it tends to stimulate student thinking better and drive more conversations which our teachers can use to guide their instruction. Our teachers achieve this by adding questions to their assessments such as “How is the exam going for you right now? Write a few words or details.” or “Did you guess or were you sure when you answered the previous question?” When our teachers began adding questions like these to their assessments, they increased the likelihood that their students saw them as mentors, an invaluable figure in their lives.

Pay Attention to Belonging Cues

Too often, educators unknowingly leave many of our students with uncertainty about if they belong or if they matter. This unintentional and invisible isolation can lead to students believing that school is a solo endeavor, leading to many school issues. Even the tiny implicit signals teachers send to students through comments or body language “can reinforce the internal narrative that they don’t know what they are doing and don’t belong in the classroom. (Felton & Lambert 2021).

A misinterpreted cue can lead to deterioration of performance or relations when there was no deliberate intent to isolate or marginalize. Although these signals are unintentional most of the time, they can still be debilitating for a student and may potentially impede future performance (Bandura 1997). Often, the perception that a student does not know something or is deficient in their ability could be due to the teacher sending cues about a lackluster performance (Bandura 1997). When teachers send deficiency-based cues to their students, they can be ashamed to admit what they do not know; they are confused, uncertain, or struggling.

How Can You Pay Better Attention to Your Belonging Cues?

As educators, we need to send a signal to our students that we genuinely care about their lives and sincerely care about their growth as human beings. You convey that you believe in your students’ abilities to succeed either directly or indirectly through the intentional transfer of content knowledge and skills, or indirectly, through cues such as eye contact, facial expressions, body language, and voice intonation (Felton & Lambert, 2021). The right cues can help students see that you are an ally and not an obstacle to their learning. (Felton & Lambert, 2021).

In his 2018 book The Culture Code, author Daniel Coyle writes that successful groups (businesses and schools alike) had three common attributes among their members:

1. Their members said they felt safe.

2. Their members said they felt connected.

3. Their members said there was a purpose to their work.

Some ideas I suggest to build these three attributes into your teaching practice could be:

1. To make your students feel safer, perhaps inactivate your formative assessment scores. In my experience, it signaled to them that it was acceptable to take risks and even temporarily fail in my class.

2. To make your students feel more connected, pause your entry into the lesson and let the students attempt to make learning independently, even for a few moments. In this way, students can build a personal state of learning that they can connect to my lesson to make sense of the content better.

3. To help your students see more purpose in classwork, consider designing your curriculum around transferable and enduring skills instead of situationally-focused content. When I re-designed my curriculum with a skills-first mindset, my students saw more purpose in the content because they understood they were learning the content to develop a more significant skill with potentially more utility in their lives.

These attributes make members of groups feel like they belong, and the same qualities should be true for your students.

Make Dialogue A Central Part of Your Practice

“When we learn and talk together, we break the notion that our experience of gaining knowledge is private, individualistic, and competitive by choosing in fostering dialogue we engage mutually in the learning partnership” (hooks, 2003). Suppose we are sincere in our devotion to getting to know our students. In that case, we should feel more empowered to ask students about their internal and external experiences throughout the learning process.

However, the societal view of a teacher tends to be as the imparters of wisdom or the possessors of proper knowledge, responsible for each student’s learning. This view leaves many teachers to consider the information in their lessons more valuable than their students’ minds and hearts. In my opinion, this is problematic as it put students in a passive role and places the burden of a student’s learning on the teacher’s shoulders, where it does not primarily belong.

How Can You Make Dialogue a More Prominent Part of Your Practice?

After many years in education, I realized that learning should be the student’s responsibility, and the responsibility of the conditions of learning should be the teachers. To make more sense of this point, I want you to think about a gardener. A gardener is someone who prunes, waters, and tends to the plant but does not tell the plant how to grow–the plant is responsible for growing itself. This gardening process should be the same in the classroom, where students learn how to develop themselves, and the teachers nurture this growth.

I found that students are more than willing to talk about their struggles and deficiencies when I asked a mixture of academic questions and personal questions. For example, I would insert reflective pauses on my assessments where I would ask students, “What new things have you realized after completing the last section of the exam? Or “do you have any questions at this point of the exam?” Asking these questions served several purposes: 1) they signaled to my students that I cared about them as people; that it was acceptable to talk about their experiences and emotions in my classroom, 2) I gathered more context about their answers and thought processes, and 3) I signaled that dialogue was a central part of my classroom.

A strategy that I used to help me use their dialogue as a central focus of my practice was to recite the phrase “Ask, don’t tell?”; meaning “Ask [students about their thinking first], [before] I tell [them advice].” (Sorensen, 2017). It was a mantra of sorts that I would say to myself as I interacted with students or provided feedback; sometimes they had such fantastic insight that they did not even need my advice! Repeating this phrase helped me build the mindset that I should be more of a reactor to student thinking and performances and not merely a deliverer of information or evaluator of their work. I was to act as a supportive presence for students who tried to make meaning, explored new experiences, emotionally worked through setbacks, and faced new challenges.

Closing Thought

As I close this article, I want you again to picture your classroom. However, as the image becomes clearer in your mind, I want you to ask yourself this question, “Am I teaching to my students, or am I teaching with students?” A teacher is likely to have more experience and expertise than their students, but that doesn’t mean they don’t have any. This erroneous assumption leads teachers to believe that their students are empty vessels and are waiting for the teacher to fill their minds with the teacher’s expertise (hooks, 2003). In my experience, it is teaching with students that matters most in education, where teachers create meaning and knowledge with their students. I invite you to think about meaning as an emergent concept resulting from interdependent collaboration, relational pedagogy, and productive discourse. When I did these central practices in my classroom, they transformed my classroom culture, my students’ engagement, and even me as a person.

Bandura, A., Freeman, W. H., & Lightsey, R. (1999). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control.

Chapman, B., & Sisodia, R. (2015). Everybody Matters: The extraordinary power of caring for your people like family. Penguin.

Coyle, D. (2018). The culture code: The secrets of highly successful groups. Bantam.

Espinoza, R. (2011). Pivotal Moments: How Educators Can Put All Students on the Path to College. Harvard Education Press. 8 Story Street First Floor, Cambridge, MA 02138.

Felten, P., & Lambert, L. M. (2020). Relationship-rich education: How human connections drive success in college. JHU Press.

Freire, P. (1996). Pedagogy of the oppressed (revised). New York: Continuum.

“Great Jobs, Great Lives: The 2014 Gallup-Purdue Index Report,” Gallup and Purdue University, 2014, https://www.gallup.com/file/services/176768/GallupPurdueIndex_Report_2014.pdf.

Hooks, B. (2003). Teaching community: A pedagogy of hope (Vol. 36). Psychology Press.

Schlosser, J. A. (2014). What would Socrates do?: self-examination, civic engagement, and the politics of philosophy. Cambridge University Press.

Sorensen, M. S. (2017). I HEAR YOU: The surprisingly simple skill behind extraordinary relationships (First Edition.). Utah: Autumn Creek Press.