Responding to Trauma and Responding to Evidence – Both Needed, Both Possible

As regular readers of the STAC blog posts offered by my colleagues and me, you won’t be surprised to read the next sentence. Assessment is one of the most stress-inducing activities educators put students through. Perhaps some of you might even have some uncomfortable reactions when you recall some of your own test experiences. I should qualify this with the notion that I’m talking about assessment done poorly – the type of assessment I define as a number chase, instead of effective assessment which I believe is an evidence chase. But first, let me connect the dots to the title of this post.

In our newly released book Trauma-Sensitive Instruction: Creating a Safe and Predictable Classroom Environment, John Eller and I share a definition of trauma that really stopped us in our conversations because it was so powerful. The definition is from the work of Kathleen Fitzgerald Rice and Betsy McAlister Groves (2005) and states: “Trauma is an exceptional experience in which powerful and dangerous events overwhelm a person’s capacity to cope” (p. 3). The current stress we are all experiencing (and to varying degrees) brought on by the health pandemic far outweighs the stress induced by ineffective assessment practice. However, the combination of these two – poor assessment practice and additional trauma from the pandemic – may combine to negatively impact students to the point that their progress and academic growth might never recover in their remaining school years. It doesn’t have to be that way.

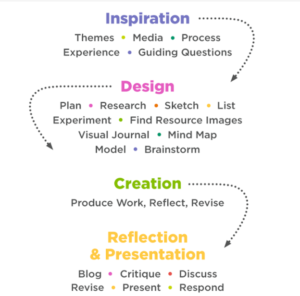

In my work with teachers, I’ll often hear that the constant stress and lack of stability sets up students for difficulties in calming down in order to feel safe, learn, and give their best when it comes time to performing on assessments. Teachers, then, would be wise to invest in assessment design that does not depend on a “one shot, achieve or fail to” test. Instead, formative assessment – the practice before the performance – must be a part of the evidence gathering, not just for students experiencing trauma, but for all students.

The impact of the pandemic was not evenly distributed nor evenly felt. For some of our students (and colleagues) it reinvigorated past traumatic experiences almost incapacitating any opportunity for progress. For some students, the extended trauma exposure resulted in what Jim Sporleder and Heather Forbes (2016) refer to as toxic stress. Toxic stress can lead to issues that can impair students’ normal development and success in the classroom, including their ability to focus and respond appropriately to teacher requests. The potential for assessment to be inaccurate or incomplete is very high. In Trauma-sensitive Instruction we offer many scenarios like this one:

“Laura, a seventh-grade student, lives in a home where her father drinks excessively and comes home drunk. When he gets home, he is both verbally and physically abusive to Laura’s mom and any of the children he sees. Laura normally knows that when he comes home, it’s a good idea to stay out of his way and try to be invisible. She usually withdraws from the situation and tries not to cause a lot of issues.

In her classes, Laura uses similar behavior. Even though she may not understand what she is learning, she is reluctant to ask questions or get clarification. When working in groups, Laura contributes little to the conversation and goes along with the ideas of the group. She is reluctant to make eye contact with people (adults and peers) and appears to be disconnected and isolated.”

Relationships are critical

How might the teacher respond to Laura’s actions while also committing to gathering good evidence to assist her on her educational journey? If Laura is disengaged and disconnected, her teacher may not be able to assess what she knows. Somehow, her teacher has to be able to reduce her stress to be able to get an accurate read on her progress.

Again, the focus on why we assess comes into play. One of the powerful outcomes of a fair an equitable assessment process is the development of a positive relationship between teacher and student. The more assessment is viewed as an opportunity to demonstrate learning and to progress from “not yet” to “proficient”, the greater the view that teacher and student are on a journey together. In our research for Trauma-sensitive Instruction one of the keys that emerged to help buffer against adversity is having warm, positive relationships, which can prompt the release of anti-stress hormones. The choice to have assessment as a stress inducer versus a stress buffer comes down again to how the evidence is used by both the teacher and the student. If teachers can help the student see how assessment data can help them learn, it may cause less of a stressful reaction. If the student thanks that assessment is being used only to label or sort them, it will not be seen as positive or productive, and they certainly won’t capitulate.

We also know that the trauma that came with the health pandemic did not arrive on every doorstep equally. The Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP) suggests that “COVID-19 exposures were significantly different across race and household income strata, with Black, Latino, and low-income families reporting higher rates of COVID-19–related stressors, which they attributed to systemic racism and structural inequities…” The trauma-aware schools project further suggests, “Symptoms resulting from trauma can directly impact a student’s ability to learn. In the classroom setting, this can lead to poor behavior, which can result in reduced instructional time and missed opportunities to learn.” It’s important then, that educators avoid overemphasizing the importance of tests and exercise caution to avoid overemphasizing the consequences of failure. The messages educators use to communicate about tests matter, and efforts should be made to reduce students’ anxiety and increase students’ self-efficacy beliefs. The message should focus on the role of assessments as a measure of students’ knowledge and ability at this moment.

Know what to look for–and how to react

One of the key body reactions to trauma occurs as a result of the fight-or-flight response. Educators often see this reaction during test time with those students who arrive and seem to “power down” immediately upon receiving their tests. They may quickly do as much as they can and turn in an incomplete exam or they may just put their name at the top and stop there. When this level of trauma is occurring, the body may be releasing cortisol which keeps the body on alert and primed to respond to the threat. It is important to note here that while the body is primed to respond to the threat, the control center of the brain, the pre-frontal cortex, is shut down. This is the place for logic and reasoning, key skills needed for assessments.

In a paper that focused on high-stakes testing, the authors (Jennifer A. Heissel, Emma K. Adam, Jennifer L. Doleac, David N. Figlio, Jonathan Meer) found that “Students whose cortisol noticeably spiked or dipped tended to perform worse than expected on the state test, controlling for past grades and test scores.” So, if summative tests unfairly penalize students who are experiencing high levels of trauma, it might be reasonable to conclude those tests aren’t generating the evidence we need them to, and they might not be aligned with the formative evidence we already have. The authors go on to state “A potential contributor to socioeconomic disparities in academic performance is the difference in the level of stress experienced by students outside of school.” This means as educators we have to be mindful that students will react differently to similar traumatic experiences and may need different kinds of support from us.

Let me summarize by going back to the title of this post. It’s important for educators to recognize the need to pair trauma-informed teaching with assessment processes to ensure we are not adding more trauma to our students’ lives. Strategies to consider include communicating the purpose for assessment, providing a calm and predictable classroom environment, building and leveraging positive relationships with students, and recognizing when students are under stress and helping them to relax in order to make assessment a natural part of their learning journey. These and other trauma-informed practices will not only help them do better, but will also help them build the resilience they need to be productive and well-rounded adults. Adults who have the capacity to break the trauma cycle for their own children. By the way, these practices, when fully implemented, will benefit ALL learners not only those whose lives have been impacted by trauma.

https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/news-perspective/2021/04/covid-studies-note-online-learning-stress-fewer-cases-schools-protocols

https://traumaawareschools.org/impact

Testing, Stress, and Performance: How Students Respond Physiologically to High-Stakes Testing

https://justicetechlab.github.io/jdoleac-website/research/HADFM_TestingStress.pdf

Sporleder, J., & Forbes, H. T. (2016). The trauma-informed school: A step-by-step implementation guide for administrators and school personnel. Boulder, CO: Beyond Consequences Institute.