Over these past few months, I have come to embrace one distinct truth: things are predictably unpredictable right now. From the method of instructional delivery, to student access and opportunity to receive academic and emotional support, the dynamics around how we are able to “do school” this year have presented themselves as anything other than consistent and reliable.

Yet the uniqueness of this moment has welcomed opportunities for innovation and creativity. We are utilizing information we already have about “what works” and applying it to new scenarios and problems to be solved. It has further elevated teachers’ relentless pursuit of student achievement and highlighted new strategies, techniques, and frameworks that build resolve and resilience in each other as well as within our students. We have dug deeper into our emotional reserves and been open to pedagogical practices that enable our content to come to life in ways that align with our new learning environments. It is phenomenal to watch teachers all across this country lean into the power of teams, as they look at the student faces in front of them and know that today is not going to be the day that we leave a student behind.

This observation of teacher practice reminds me of a scene from one of my favorite childhood stories:

“You see, so many out-of-the-way things had happened lately, that Alice had begun to think that very few things indeed were really impossible.”

Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

Doesn’t the first part seem to describe our current environment well? Many of us may feel similar to Alice in a different regard, as though we are falling down the rabbit hole and wondering when our two feet will once again be firmly planted on our instructional ground. Yet, in the middle of this freefall, let us remember: very few things indeed are really impossible.

As we have been inundated with the multitude of things this year that have been impossible to control, here is a strategy to help you focus on what is possible: using learning progressions to move each student to mastery.

Over the past few months, the most frequent question from teachers—by far—has been, “How can I be sure that my students are learning what I’m teaching?” Whether distance, in-person, or hybrid, the rigor of the learning targets and standards remains the same. What we are teaching, and the level we need to teach it to, has not changed. It’s important for us to remember that part. Our expectations for students are constant. Now we just need to figure out how to teach to and monitor those expectations. Easy, right? Let’s just agree that some days are probably better than others. But we can make it easier with this strategy: building a learning progression toward mastery. Read on for an example of this in practice.

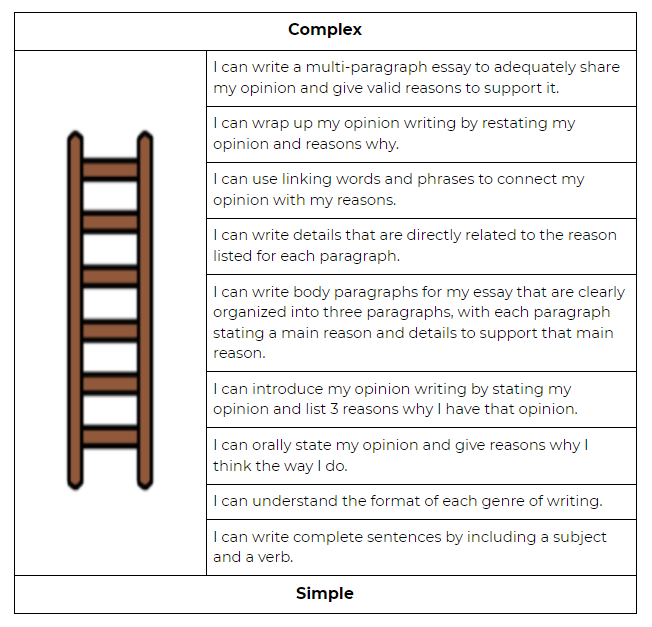

We’ll use a ladder visual to help us build the learning progression. Our colleague, Nicole Dimich, introduces the ladder in her landmark resource, Design in Five: Essential Phases to Create Engaging Assessment Practices, as a means for teachers to think about the pathway to proficiency. Along this pathway, teachers liken the learning targets (which they collaboratively unpacked from their essential standard) to rungs on a ladder, representing how each target is a step closer to proficiency. With each step, the cognitive rigor increases.

I recently worked with the third/fourth-grade literacy team at Valley Springs Elementary in Harrison, Arkansas. Take a look at their work through this process, shown below. The team was working on opinion writing, using the following standard:

W.3.1 Write opinion pieces on topics or texts, supporting the opinion with reasons.

- W.3.1A. Introduce the topic or text they are writing about, state an opinion, and create an organizational structure that lists reasons.

- W.3.1B. Provide reasons that support opinions.

- W.3.1.C. Use linking words and phrases (e.g., because, therefore, since, for examples) to connect opinion and reasons.

- W.3.1.E. Provide a concluding statement or sections.

From this standard, the team unpacked these learning targets:

- I can write complete sentences by including a subject and a verb.

- I can understand the format of each genre of writing.

- I can orally state my opinion and give reasons why I think the way I do.

- I can introduce my opinion writing by stating my opinion and list 3 reasons why I have that opinion.

- I can use linking words and phrases to connect my opinion with my reasons.

- I can wrap up my opinion writing by restating my opinion and reasons why.

- I can write a multi-paragraph essay to adequately share my opinion and give valid reasons to support it.

- I can write body paragraphs for my essay that are clearly organized into three paragraphs, with each paragraph stating a main reason and details to support that main reason.

- I can write broad yet distinct reasons that support my opinion.

- I can write details that are directly related to the reason listed for each paragraph.

From this point, the team reviewed the learning targets and reorganized them into a learning progression from simple to complex, along with the evidence needed for a successful pathway toward proficiency. This process improves clarity of what is expected, which in turn improves performance, for both teachers and students. Dimich (2015) further claims,

For students to benefit, teachers share with students the learning goals and the student work required to show an understanding of them. This creates a road map for students who, in turn, gain a clearer idea of how the learning goals they are working on (through instructional activities and formative assessments) are going to help them be successful on the summative assessment. When planned in this way, teaching to the test or task is not a limiting practice, because the learning is driving the assessment, as opposed to the test driving the learning. (p. 38)

The team placed their learning targets in order from simple to complex as follows:

The team agreed that this is the learning progression they will follow as they monitor student performance on this standard. The top of the ladder shows what students need to do to demonstrate a comprehensive understanding of this particular standard. The learning targets below describe the pathway to proficiency of the standard.

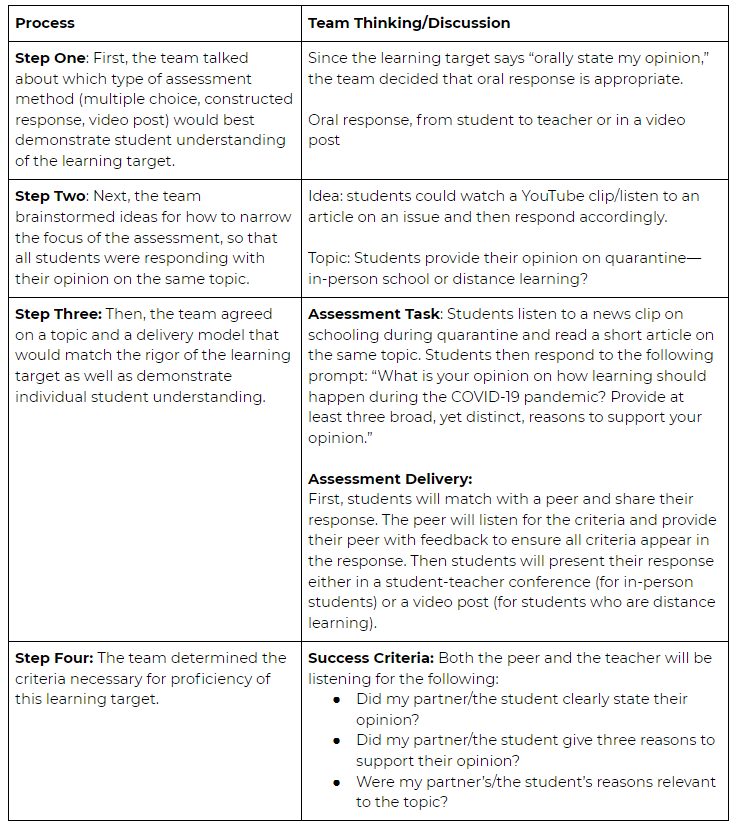

The team also recognized that some of these learning targets are so fundamental to mastery of the whole standard that they need to generate common formative assessments in order to monitor students’ progress along the pathway. The table below shows this team’s thinking as they planned for their first common formative assessment:

Learning Target for Common Formative Assessment (CFA) #1: I can orally state my opinion and give reasons why I think the way I do.

Of course, the final step here is that the team discusses the student responses and determines how close students are to meeting their proficiency expectations. The team then generates a plan for responding to any students who may need additional support, in order to master the next learning targets on the ladder to proficiency.

While many “out-of-the-way” things are happening lately, student learning—even in the middle of a pandemic—is indeed possible. Work with your team (or a trusted colleague) to determine how students climb that ladder of proficiency for each essential standard. If you show students the pathway, they will eagerly step on each new rung as they make their way to the top. This strategy can support you and your teams to invite hope, possibility, and confidence for your students as they climb that ladder toward achievement.