Grading and assessment is often very personal—to students, to parents, and to teachers. I wear (as many of us do) many hats: parent, trainer, facilitator, author, and learner. And, I am all too aware of how my own children’s confidence and motivation is impacted by assessment.

In the absence of clear descriptions, students often make their own meaning of what those comments, symbols, or quantities mean. Those interpretations influence what students believe about their abilities. When they feel confident, learners will often persevere until they figure it out or they will review something they got wrong to understand what to do differently. On the other hand, learners that lack this confidence will often become incredibly frustrated and stressed, or even shut down. Even more damaging, they may begin to believe they are “stupid” or “inadequate.” Teachers have incredible power to shape and empower confidence and motivation to combat this kind of negative thinking.

Before we look at the ways we can do that, I want to share a moment I experienced with my fourth grader. Here’s how the conversation played out:

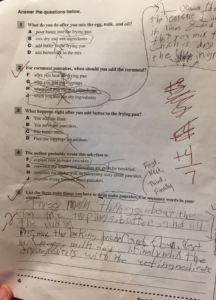

I looked through Chase’s Friday folder, which was jam-packed with work. Numbers were written at the top of each assessments and worksheet: 16/17, 17/18. We were both feeling good despite the fact there were no descriptions of learning. The number correct suggested he understood something.

Then, we got to the reading test. Chase said (with exasperation and a sense of ‘it’s going to be bad’), “This is the most important one; what did I get on that?” I glance and realize his gut was right on. I cautiously observe, “Well, it’s four out of seven. Let’s look a little bit at what happened.”

I put my teacher hat on at this moment and started thinking about how we could dig in and figure out what he knows and where the misunderstanding occurred. Chase was not impressed with my attempt at turning this into a learning opportunity. He emphatically explained (and yes, he did throw himself on the floor because we are a bit dramatic at times): “That’s horrible. I suck. I’m stupid.” I’m not revising any words here. As a mom, my heart broke a bit at the thought that this seven-point quiz could cause this type of stress and frustration.

This moment reminds me, again, of the impact of quantities over qualities on student learning, student perceptions, and student motivation. Motivation can be negatively impacted by noting the number wrong, using percentages, or even using standards-based grading marks or symbols (whether it is a 4, 3, 2, 1 or an E, M, P, N) when there are no learning descriptions (learning targets, scales, rubrics) to help students and even families make sense of them. In the absence of descriptions, four out of seven still means about 60 percent, and that translates to “not good” or “I suck.”

When the goal is clear communication—whether to get better or to show proficiency at a moment in time—quantitative assessment falls short. The notion that quantitative marks or symbols will motivate is also misguided, especially for students who have not experienced much school success or who don’t know what to do to gain more points. It just doesn’t work for kids who need more targeted instruction. It is devastating and demoralizing, and a teacher will need to work three times as hard to help those students build enough confidence to believe that if they try to do something different, it will help.

Hattie and Timperely (2007) revealed this in their review of feedback research 10 years ago. And, I experience it now as I try to help my son recover from the relentless onslaught of quantitative feedback about how he isn’t reading fast enough or how he isn’t getting enough questions right. I slow down and help him see that none of these things are true, but the numbers are what he sees. He can easily do the math and know that he isn’t getting it. And, without a deeper dive into why and what’s next, it is left up to him to try to figure out how to get the right answer. Teachers are working incredibly hard, and I know there is no intended harm. And, I also know that Chase is distractible. Does it sometimes take him longer to understand the directions and get the point? Yes, but what might a little description instead of numbers do to his motivation and achievement?

There are urgent and compelling reasons to shift to qualitative assessment. As educators, we want to clearly communicate with parents and families at home so they are empowered to know how to help their children make sense of feedback and build on strengths and develop confidence. We want to send messages that quality matters and getting something faster doesn’t necessarily mean smarter and being thoughtful doesn’t mean a child is slow.

How we handle assessment is the difference between confidence and achievement and struggle and defeat. I get that teachers are under tremendous pressure. It’s time for leaders to protect our teachers from this onslaught of devastating test score use that requires them or makes them feel the need to quantify everything and then pass on that stress to students.

With a few simple maneuvers, teachers can offer students targeted information that will help them change the way they see their work, focus more on learning, and eventually change the mind of a student (who may feel defeated or even “stupid”) to see themselves as a confident learner that, with some specific work, can learn more.

-

- Make the learning transparent

- Write the learning target or learning goal of any assessment, worksheet, or activity on any document given to students.

- If you use scales or descriptions of learning such as in a standards-based marking system, describe what a 4, 3, 2, 1 means in terms of learning (not in terms of how many items students got right).

As an example, a quick deconstruction of the test my son took revealed the following possible learning targets:

- I can identify the order of events in a text. (items 1, 2,3,5)

- I can generally understand what the text is literally saying. (item 2)

- I can identify the author’s main point. (item 4)

The table below could have been a cover page provided to the students along with the quiz. This would have provided Chase a snapshot of his performance in terms of learning rather than the number right and wrong. He might have said he could identify the author’s main point and still needs to work on sequence words. In truth, he needs to learn how to read the question to the end.

Learning Goals Items Student Score I can identify the order of events in a text. 1, 2, 3, 2/3 I can generally understand what the text is literally saying. 5 1/3 I can identify the author’s main point. 4 1/1

- Make the learning transparent

-

- Ensure assessments/questions/tasks are at grade level

- Look at your standards and write a learning goal to that level.

- Revise or add questions, tasks, and items to give you information on the level of understanding a student has at that grade level.

- Ensure a basic level of engagement and relevance. When reading ensure the text provides opportunity to analyze what is intended at a reasonable and appropriate level.

Students need ample time to learn and grow in tasks at their grade level. Provide students opportunities to engage in this work and provide scaffolded feedback and instruction to push their learning to the next level. If they need additional instruction on prerequisite learning, teachers provide that as needed.

On the fourth-grade reading quiz, all three of the initial learning goals are below grade level. Often the actual item or task itself will signal a level of interpretation. Multiple choice items require a low level recognition (most often) of what was in the text. For this assessment, a better match for fourth graders might be, “I can explain how sequencing or logical order helps me understand a text.”

Then, you may keep the lower level items to get a basic sense of comprehension and add an additional one that will tell you more. A sample question might be, “What happens if one mixes up the order of the directions in this recipe?” There is little substance in this text so this may not be as meaningful as finding a different or companion text.

- Ensure assessments/questions/tasks are at grade level

-

- Analyze student work for misconceptions, growth areas and next steps.Work with your colleagues and analyze samples of student work to understand what the root cause of students not achieving or achieving. Then provide students feedback or next steps to push all students to the next level. It is through the collaboration process that we get better at identifying or interpreting what learners know and what they need to work on. From the teacher’s marking, we learn Chase got question 2 wrong:

For cornmeal pancakes, when should you add the cornmeal?

a) After you heat the frying pan (My commentary: You could say this was true. It’s not the best answer, but sequentially could be accurate. However, what does this tell us about understanding if students chose this answer? Quality multiple choice distractors will potentially tell you something about student misunderstanding.)

b) After you add the toppings (My commentary: This is a more obviously wrong answer. A student who chose this may have randomly guessed, but you would have to ask to understand why.)

c) When you mix the wet ingredients (My commentary: This is not wrong, but just not the answer that requires some inference. You most likely will mix the cornmeal with dry ingredients. It assumes students know cornmeal is dry. It’s the order that may be in question.)

d) When you mix the dry ingredients (My commentary: Technically the right answer from the text with an inference that cornmeal is a dry ingredient and should be mixed with other dry ingredients before adding to the wet ingredients.)

- Analyze student work for misconceptions, growth areas and next steps.Work with your colleagues and analyze samples of student work to understand what the root cause of students not achieving or achieving. Then provide students feedback or next steps to push all students to the next level. It is through the collaboration process that we get better at identifying or interpreting what learners know and what they need to work on. From the teacher’s marking, we learn Chase got question 2 wrong:

- Design instruction to require action on those next steps and misconceptions.

Chase got the constructed response answer wrong. When looking at his mistake, it was clear he thought sequence words were numbers (“Three”). He named three main things and didn’t read the rest of the question to see the phrase, “What do you do to make pancakes?” He stopped at three main things, so he listed the ingredients. The teacher underlined three main things. Unfortunately, Chase had no idea what that meant, nor why he got it wrong. There was no instruction or action to help him get this. It was just marked wrong with the hope of him learning something from his mistakes.Uncover misconceptions and determine next steps to push all students to higher achievement. Weave revision and action on these next steps into instructional plans. I sat down with Chase and made him revise his work, but that won’t be realistic for all families. He was not thrilled, but it is this type of revision and revisiting that helps students process their learning.

A teacher cannot not do this type of interrogation of work on everything. Instead, identify those essential learning outcomes and choose moments to dive a little deeper (with a maneuver or two). If you do, student confidence and achievement will soar.

Reference:

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112.