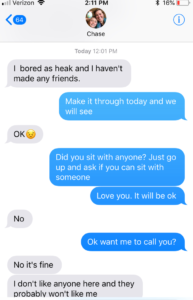

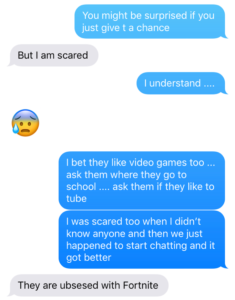

When you are unsure, not feeling confident, and scared no one will like you, it can be hard to get started. My son, Chase, is a fifth grader, and we signed him up for a basketball camp. He went alone and didn’t know anyone. As can be predicted, he was very nervous. Here is our text exchange. His messages are in gray, and my responses are in blue:

My initial thought when I received the text was to save him from this uncomfortable situation. I was kicking myself for not planning earlier and getting a friend to go with him. After a moment, I was thinking this could be a great experience for him to learn how to connect and engage, so I gave him a few things to do and say to connect with kids. He initially did not want to do this and said no. It became clear he was scared. After affirming that feeling afraid in these situations is normal, I provided just a little bit of encouragement: “You just might be surprised if you give it a chance.” He was protecting himself by saying he didn’t like them and they wouldn’t like him. Again, this was his fear talking. It took no more than a little push and a couple of ideas, and he had a friend.

Why do I use this as an introduction to a blog about assessment? Some of our most powerful moments with students happen when they are feeling vulnerable, not confident, and a bit uncomfortable. They need a little push, a little feedback, or a little direction to figure out how to connect or learn or find some success. While feedback is incredibly powerful, it does not have to be this big thing that takes hours outside of school to accomplish.

In fact, the notions of feedback and intervention are integrally related. I was facilitating some conversations around planning interventions when I realized that we are, at times, trying to make intervention systems something complex, which seems unattainable and overwhelming. Structures and strategies are certainly important to study and implement. And interventions are at their best when teachers use evidence and observation of where students are—who they are, what makes them tick, what they know, and what their gaps are—to help them connect.

It could be that they need additional time and support with specialists. Or it could mean that teachers listen and notice where the disconnect is, providing some time, ideas, and support to guide students in making that connection. Interventions can be moments.

Five Tier 1 Prevention Ideas

Check out these five strategies that could be considered Tier 1 prevention strategies.

1. The Warm-Up

Individual teachers or collaborative teams identify a concept that is essential, hard to teach, hard to learn, and worth more instructional time. They choose items or tasks (just a few) to administer to students as an exit ticket. The team meets to pile the exit tickets by misconception or what the exit ticket indicates students need to work on (Vagle, 2015). For each group, the team or individual teacher plans a 15-to-20-minute warm-up for the following day. Students get the warm-up based on how they did on the exit ticket. The “intervention” from the exit tickets may include a short agenda, where students watch a quick video on how to solve a problem or view examples of a well-written thesis statement. The quick video may even be a teacher modeling how to fix a common mistake. Then, students may fix their exit slips and try a couple more items to see if they now understand. The teacher observes and provides feedback in the moment as students need help on their personalized warm-up.

An Example of the Warm-Up in Action

A science collaborative team determined the most essential learning target of that week the day before they meet. On the day before their next meeting, each teacher took ten minutes at the end of a class period and asked students to write out an exit slip. They asked them to respond to a question or solve a problem that reflects the learning that was to occur that day. The team’s goal was to get a snapshot of what their students understand (and don’t). The team met and analyzed the results and planned instruction based on the misconceptions learners revealed in the exit tickets. The next day, during their 10-to-15-minute warm-up, students worked in groups based on what they needed more work on.

2. Four Corners (Erkens, 2016)

The teacher team gives students a review test, which is organized by learning target and essential outcome. Students review the test and can easily see which outcomes they need to work on and which they still need practice on. After students have reviewed their test and identified the essential outcome they still need to work on, Ms. Tanaka calls for four corners for each essential outcome.

Students move to the corner (corners are clearly labeled and maintain that consistent label with each use) that best represents how they achieved on the learning outcome. Their task once they arrive in the appropriate corner is to generate questions with their peers in that corner (quickly—they only get about two minutes total) about what they are learning and then to ask those questions, in an effort to try to stump the teacher.

Ms. Tanaka has found that the questions they ask truly reflect the level of understanding she would anticipate from each of the corners:

- Stop: “I am totally confused.”

- Slow Down: “I understand some of it but couldn’t pass a test today.”

- Keep Moving: “I’m getting it, and I wish we wouldn’t have too much homework about it.”

- Let Me Help: “I understand it and could teach it to my friends.”

Each corner then reports out their questions. Ms. Tanaka has observed that the questions they ask seem to inform the thinking of the other groups, generating good class discussion and a healthy sense of collaboration.

3. Observation for Tier 1 or 2 Interventions

Socratic Seminar or Class Discussion (tracking tool by Vagle, 2009)

In this discussion method, students are required to lead and sustain the discussion. After reading a text or introducing a topic, the teacher poses a question. The students then respond and continue the discussion by asking their own questions, commenting on each other’s comments, and offering their own connections and understanding of the text or topic.

In the beginning, teachers may give each student three comment cards and one question card. Before the discussion begins, the students may jot down possible comments and a question to add to the discussion. Once they offer a comment or a question, they toss the card in the middle. When they are out of cards, they must wait until each student has played all their cards to enter the discussion again. This allows everyone a chance to participate.

After teachers have tracked students’ discussion and understanding of the text, they meet to share their observations and charts. From there, they identify groups of students who need to work on different essential concepts.

One group may need to work on articulating their understanding of the basic ideas in the text. Another group identified may have the basic idea of the text but need to work on posing questions to push ideas in the text. Another group may understand the basic ideas in the text and how to ask questions but need to work on building on ideas and making connections. The final group may need enrichment.

Teacher teams can use observation of dialogue or any other activity to identify the essential outcomes students have mastered and those that need attention. Planning intervention from these observation checklists can be a Tier 1 or 2 intervention.

Other considerations:

- Address quality and not-so-quality questions, giving students examples of both so they understand what kinds of questions engage discussion as well as stop them.

- If the discussion is going too fast, kids aren’t connecting each other’s responses. Slow it down by having students summarize what the student before them said and then offer their comment or discussion.

- In tracking and observing this type of discussion, a teacher may have a chart with all student names in the first column (see below) and what the teacher is hoping to hear from each student in the other columns. As the discussion ensues, the teacher is marking down the extent to which students are engaging in quality discussion.

Teacher Tracking Form

| Student Names | Students’ words show understanding of the text:

3—Right on; reflects understanding of the text 2—Mostly accurate 1—Some key inaccuracies |

Students’ questions clearly push on ideas in the text:

3—Questions help push beyond what’s written literally in the text (prediction and inference) 2—Questions help students make some connections 1—Questions ask students to recall explicit facts in the text |

Students are building on or questioning other student comments

3—Comments or questions show students are trying to understand or evaluate other student responses 2—Comments or questions ask for clarification 1—Comments offer another example of a student’s connection |

| Student 1 | |||

| Student 2 | |||

| Student 3 | |||

| Student 4 | |||

| Student 5 |

Tracking Misconceptions

This Instructionally Agile Feedback Chart is another example of how to use observation to identify misconceptions that lead to intervention. Again, the team would analyze these charts and develop interventions for those students needing the various interventions on misconceptions (cited in Erkens, Schimmer, and Vagle, Instructional Agility, 2018 and adapted from Fisher, Frey, & Pumpian, 2012).

| Learning target: I can describe and support the central argument of a scientific text

Instructional Activity (Assessment Conversation): Learners read a text on the DNA findings that aided cancer research. Learners engage in a small-group dialogue and are individually creating a concept map with explanations; the teacher is noting evidence of understanding and error, as well as levels of confidence. The teacher uses the student initials to indicate the errors that student is making or that the student has reached mastery. This data can be used to form groups for instruction, or the teacher can pull students aside to support them throughout instruction. |

|||||||

| Error | Hour 1 | Hour 2 | Hour 3 | Hour 4 | Hour 5 | Misconceptions | Interventions |

| Summarizing the sequence of events | NT, SW | JS, LM | RR, TZ, SO, SJ, PW | JF, DS, MN, PS, LD, DD, FS, DA | |||

| Identifying the general topic versus the argument | TN, KL, OH, AM, PS, GJ | GH | JK, LS, DD, BA, WD, FW, PS, NF | KL, DZ | FD, SK, BB, LD, ES, JO, PW, DS, KS | ||

| Providing general explanations that loosely tie but don’t support the argument | KS, TM, BH, WA, FD, TP, EW | PT, NV, LS, MW, FA | LS, RV | EF, PK, SW, GJ | NT, HJ, KW, VS, TU | ||

| Others? | |||||||

| Confidence: Students show mastery but are seeking approval or wanting someone else to tell them what to do | PT, NV | SW, GJ

|

JC, NT, LE, RV, BD | ||||

| Showing mastery | VC, MS, MW, ZP, EF, AD | PE, RV, CV, MV, LJ, DE | CC, BA, DD, WP, SS, VM | KL, MN, SD, ED, PS, OS | KL, DS | ||

4. Criteria for Problem-Solving & Student Reflection (Gregory, Cameron, Davies, 2011, p. 55)

The teacher engages the class in a discussion to identify the criteria for the problem. Students identify characteristics of solving the problem. Then, individual students identify what’s working, what’s not, and what’s next based on the criteria. Here is a sample from the book Knowing What Counts: Setting and Using Criteria.

| Criteria for PROBLEM SOLVING | What’s working? | What’s not? | What’s next? |

| Understand the problem | You knew what to look for | ||

| Choose a strategy that works | You tried drawing diagrams and underlining important words | Think back to the problems we did on p. 11 or go talk to Jeremy | |

| Find a correct solution and explain how you get it | You didn’t go quite far enough. There’s one more step. | ||

| Give examples of this kind of problem outside the classroom | Your example was accurate. |

The collaborative team identifies all the students who need to work on the same criteria and plans a “prevention” instructional experience, so learners who need to improve in that area get the time and support. For example, the team has identified 30 minutes each Friday that is protected to respond to those identified areas of need.

5. Scenario: The Final before the Final (Erkens, 2016)

Ms. O’Malley gives her final exam two weeks in advance of the end of the term. Those students who do not pass the exam then spend the next two weeks identifying and closing their gaps as they prepare to retake the test (different test, same learning targets). The collaborative team identifies interventions for each essential outcome beforehand, using their analysis of the errors students made to guide the suggested interventions. Those students who pass the exam move to enrichment activities.

To Ms. O’Malley’s surprise and delight, many students who pass the exam the first time choose to coach a student who did not pass as their extended learning opportunity. Her collaborative team analyzes the results and plans lessons and activities for each essential learning outcome on the final exam. The chart below can help guide that work.

Teacher Analysis and Planning Chart

| Essential Outcome | Items | Number of Students NOT Mastering this Essential Outcome | Potential Misconceptions | Tier 1 Intervention | |

Kindergarten Anecdotal Observations (Exam before the Exam)

High-Frequency Words Essential Learning Outcome

| Essential Outcome | Observations | Misconceptions | Tier 1 Intervention | Tier 2 Intervention | |

| I can ask and answer questions about text | |||||

| I can read high-frequency words | |||||

| I can write complete thoughts |

References:

Erkens, C., Schimmer, T., & Vagle, N. D. (2017). Instructional Agility: Responding to assessment with real-time decisions. Bloomington, IN. Solution Tree Press.

Erkens, C. (2016). Collaborative common assessments: Teamwork. instruction. results. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press.

Erkens, C. (2014, May 30). The power of homework as a formative tool. Accessed at http://anamcaraconsulting.com/wordpress/2014/05/30/the-power-of-homework-as-a-formative-tool on May 30, 2014.

Fisher, D., Frey, N., and Pumpian, I. (2012). How to create a culture of achievement in your school and classroom. Alexandria, VA: Association of Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Gregory, K., Cameron, C., & Davies, A. (2011). Self-assessment and goal setting (2nd ed.). Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press.

Ruiz-Primo, M. A., and Li, M. (2011). Looking into teachers’ feedback practices: How teachers interpret students’ work. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans, LA.

Vagle, N. D. (2015). Design in five: Essential phases for engaging assessment practice. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press.

Vagle, N. (2009). Inspiring and requiring action. (Chapter 9). The teacher as assessment leader. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree.