Each day, we make choices. Some decisions yield good outcomes, and some do not. Whatever the result, we know these decisions are the ones we made; we considered the situation and chose. However, this sense of agency in our choices may be illusory. Researchers Banaji and Greenwald found that “our rationality is often no match for our automatic preferences” (Pg. 42, 2016). Researchers find that we make decisions less from our conscious processing in other studies (Maitland & Sammartino, 2015). Instead, much of what factors into our choices result from quicker, more automatic processes that are less available in our conscious thinking (Blumenthal-Barby, 2016). These automatic processes are what is commonly known as heuristics.

At their core, heuristics are “judgments of likelihood in the absences of deliberative intent” (Fischhoff et. al, 2002. p. 5). They are a kind of natural assessment that can influence the judgment of a person, place, or thing without being used deliberately or strategically (Blumenthal-Barby, 2016). For example, someone may pass a broken-down building as they walk to work. Upon seeing the building and without the time to thoroughly investigate the reason for its condition, they will rely on heuristics and conclude that fire destroyed the building and that it is unsafe. When someone does this, they make generalized judgments about the building without thoroughly investigating its history, which, as you are probably thinking, can sometimes be inaccurate.

Heuristics and Student Learning

So, why is a discussion of heuristics relevant for teaching and learning? Since teachers are regularly under stress from classroom demands, they often rely on heuristics to make conclusions about students, their learning, and the quality of their work. While these conclusions are usually correct, they can also be incomplete, inaccurate, or even create a distorted reality of the learning environment (Tversky & Kahneman, 2013).

Even more problematic is that heuristics are vulnerable to biases (Maitland & Sammartino, 2015), such as race, gender, and class. Heuristics can activate biases which can impact teacher evaluations of their students and perhaps influence classroom interactions. For example, a student’s perceived race may trigger a heuristic response, possibly leading to a shifted standard against which the teacher grades the student’s work (Quinn, 2020).

You can establish unbiased learning relationships through student-centered teaching techniques to minimize the effects of heuristics and reduce their susceptibility to implicit biases. Although there are numerous techniques to mitigate heuristical effects on your practice, I will discuss a few of the more salient methods.

Teach to Students’ Core Identity, Not their Role Identity

Students often feel the tension between their core identity, who they naturally are, and their role identity, or who their school suggests that they are (Turner, 2012). These two roles are further described in the figure below:

Figure 1.1

| Core Identity | Role Identity |

| Who they are | Who school sees them as |

| Who they want to be | Who school needs them to be |

Adapted from Johnathan Turner (2012)

This tension can cause a mental duality (Emdin, 2021) that is often difficult to manage academically, socially, and emotionally due to the internal conflict it may cause. Students caught in this duality may ask themselves, “Am I valued for who I truly am?” or “Am I only valued when I take on the role the school wants me to take on?” This internal dialogue can be exhausting and may lead to behaviors that, on the surface, look like disobedience; however, in reality, they are a reaction to not being respected for who they are (Emdin, 2021).

One way to respect a student’s core identity is to make your assessments operate like a conversation. I am not talking about oral assessments. Instead, I suggest that you add dialogic questions alongside your evaluative questions. Dialogic questions ask how the student is progressing, what they might be thinking, or how they may be feeling. The questions create a reflective departure that can be a reprieve from knowledge demonstration. Through these questions, students can share information to give you insight into the realities of their core identity. This information might also be relevant when you review their academic work. Examples of dialogic questions can include:

- Now that you have completed questions 1-3, how did they go for you? Were they difficult? Easy? Was there a tricky part?

- Take a breath; you’ve come a long way into the assessment. What questions do you have for me about the exam up to this point? Write them in the margins.

- How did you feel after that section? How did you feel as you worked through it? What were the ups and downs? Let me know; I always like to hear about your experience.

These dialogic questions can signal to the student that they have your unwavering support, which every student deserves. Additionally, these questions demonstrate to students that their thoughts and emotions matter to you as much as the content.

Maintain an Empathetic Perspective.

Being able to recognize and satisfy your students’ need for validation can also minimize the biased effects of heuristics. Paul Sorensen, author of the book I Hear You: The Surprisingly Simple Skill Behind Extraordinary Relationships, knew much about validation when he started writing but says, “what I didn’t know about [validation] is how starved people are for it.” Our students are no different; they need our validation to feel safe, feel connected, and develop a sense of who they are. Validation and affirmation by a trusted individual are necessary for a child’s development because those moments may act as fixtures of their self-concept. (Noddings, 2013).

An effective way to help students feel validated is to use their thinking to teach them instead of yours. I am aware that what I am suggesting runs counter to many people’s perception of the role of a teacher; however, helping students use and trust their thinking is vital for their agency development (Vaughn, 2020).

In my experience, the more I used a student’s thinking to teach them, the better listener I became. I became deeply interested in what my students had to say about their learning. I observed them become more empowered learners as they began to rely on their thoughts and emotions to learn and grow themselves. Some examples of this technique include:

- “How do you feel about your ability after doing [that performance]?”

- “Could you apply that same action [here], or do you still not think you could?”

- “That comment you just made is the key to this concept. Say that to yourself as you solve the next problem, and I think you will solve it.”

Furthermore, using student thinking instead of yours increases the chance you develop a more democratic learning environment that respects student self-expression.

Practice Reciprocity

In his book Together, Viky H. Murthy, former surgeon general of the United States, says that the “reciprocal feeling” (2020, pg. 216) that people experience in relationships is the most fundamental element of rewarding connection. Students look for reciprocity from you to feel a sense of belonging and value. Whether they see you as a central or peripheral figure in their lives, they long for your attention and acknowledgment–it is a prerequisite for learning.

Creating reciprocity goes beyond standing at your door, greeting each student as they enter, engaging them in brief conversations about their lives. True reciprocity comes from a teacher continuously capitalizing on moments (micro and macro) to demonstrate that they care (Ozcelik & Barsade, 2018, pg. 2348). Macro moments of care are easily observable and performed in classrooms; they take the forms of public praise, awards, or applause and are typically premeditated. Although the macro-moments of care are essential, the micro-moments of care can build the reciprocity that Murthy defines. These moments are not always visible but exist in our moment-to-moment interactions with students. Some examples of these micro-moments are:

- Instead of saying “Good job,” you might say, “I knew you could do it.”

- Instead of jumping directly into advice about their work, linger for a moment on something you know they are interested in before giving feedback. For example: “So you talked about camping with your family the other weekend, this problem is kind of like that experience….”

- Even a slight facial expression that acknowledges their growth or intuitive ability is an example of a micro-moment of care.

These small moments of care are not lost on students; make them a priority in your class.

Use Rubrics to Honor Student Individuality

Rubrics with detailed criteria, checklists, and uniform language can create imagery in your students’ minds that is suggestive of an ideal work product, thus suggesting sameness is what the school desires, not self-expression. Christopher Emdin, the author of Ratchetdemic, says it best, “If everybody is trying to be like somebody they are not and if the system of education is hell-bent on making everyone into a version of excellence that is about sameness, we will remain as we are swimming in inequity, struggling to make connections with young people in their communities, paying lip service to social justice and cultural relevance, and maintaining the status quo” (Emdin, 2021, pg. 14).

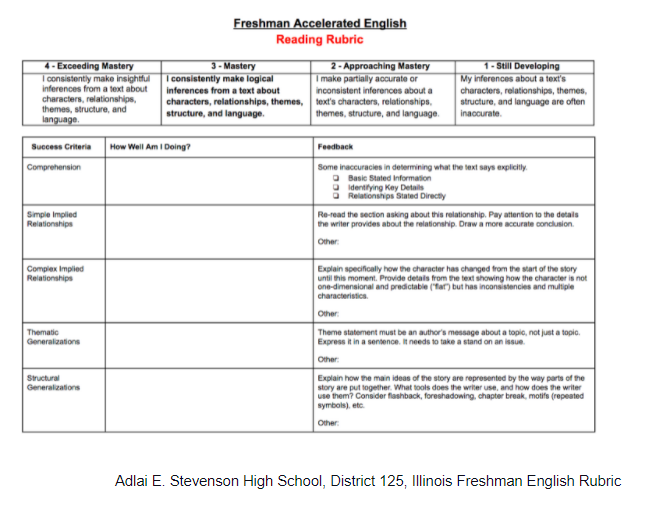

One of the more effective techniques to allow students to express their authentic selves is using rubrics. Several things can happen when a teacher gives students rubrics based on mastery of enduring skills, utilize proficiency scales, and outline success criteria. First, students can contextualize content mastery. Second, early rubric presentations can stimulate conversations with students about how they intend to demonstrate their learning. Using rubrics throughout the learning process can help democratize the learning process. Democratizing the learning process means allowing them to share their voices, self-monitor, and display their competency in a way that makes sense to them. A rubric is an essential tool to achieve this goal. An example of a rubric is seen in the figure below:

Further, students’ continuous use of rubrics can help them develop personal agency and self-advocacy. When students have a frame such as these rubrics, they learn how to monitor their progress, calibrate their self-assessments with the teachers, and contextualize their ability in the course content. Rubrics should initiate and maintain conversations about learning, not end them.

Closing Remark

Remember that “everyone you meet is afraid of something, loves something, and has lost something” (Brown Jr., 2007. p. 62). These techniques helped me remember this about my students. It reminded me that they are sentient and whole beings, not deficient and wayward souls. Time and again, these techniques helped me connect with my students and let them know I cared about them.

Resources

Banaji, M. R., & Greenwald, A. G. (2016). Blindspot: Hidden biases of good people. Bantam.

Blumenthal-Barby, J. S. (2016). Biases and heuristics in decision making and their impact on autonomy. The American Journal of Bioethics, 16(5), 5-15.

Brown Jr, H. J. (2007). Complete Life’s Little Instruction Book: 1,560 Suggestions, Observations, and Reminders on How to Live a Happy and Rewarding Life. Thomas Nelson Inc.

Emdin, C. (2021). Ratchetdemic: Reimagining Academic Success. Beacon Press.

Fischhoff, B., Kahneman, D., Slovic, P., & Tversky, A. (2002). For those condemned to study the past: Heuristics and biases in hindsight. Foundations of cognitive psychology: Core readings, 621-636.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (2013). Choices, values, and frames. In Handbook of the fundamentals of financial decision making: Part I (pp. 269-278).

Maitland, E., & Sammartino, A. (2015). Decision making and uncertainty: The role of heuristics and experience in assessing a politically hazardous environment. Strategic management journal, 36(10), 1554-1578.

Murthy, V. H. (2020). Together: The healing power of human connection in a sometimes lonely world.

Noddings, N. (2013). Caring: A relational approach to ethics and moral education. Univ of California Press.

Ozcelik, H., & Barsade, S. G. (2018). No employee an island: Workplace loneliness and job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 61(6), 2343-2366.

Quinn, D. M. (2020). Experimental evidence on teachers’ racial bias in student evaluation: The role of grading scales. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 42(3), 375-392.

Turner, J. (2012). The problem of emotions in societies. Routledge.

Vaughn, M. (2020). What is student agency, and why is it needed now more than ever?. Theory Into Practice, 59(2), 109-118.