“Something to Talk About,” recorded by Bonnie Raitt in 1990, happens to be one of my favorite songs. While listening to it the other day, I began to think about the lyrics in a different context: meaningful assessment of student conversations. Tapping into student discourse is one of the most informative means of examining student thinking, particularly with students who might be culturally or language diverse. According to Zaretta Hammond, “One of the most important tools for a culturally responsive teacher is instructional conversation. The ability to form, express and exchange of ideas are best taught through dialogue, questioning, and the sharing of ideas.” (Hammond, 2015, p.149).

There is seemingly vast potential for educators to gather authentic evidence through the observation of academic conversations. Teachers can gain valuable insights into their students’ conceptual understanding and the language skills they demonstrate in real-time, authentic conversations. But as I reflect on the various assessment practices that I typically observe, I wonder if we are capitalizing on this powerful source of information? Are educators assessing the quality of rigorous academic conversations and providing support when needed to enhance that quality?

What are Academic Conversations?

According to Zwiers and Crawford (2011), academic conversations are back-and-forth dialogues in which students focus on a topic and explore it by building, challenging, and negotiating relevant ideas. Within these conversations, educators help students develop specific skills tied to core skills, including elaborating and clarifying, supporting ideas with evidence, building on challenging ideas, paraphrasing, and synthesizing. These skills are typically specifically outlined in state ELA standards within the speaking and listening strand. For instance, the following anchor standard in Speaking and listening serves as the “end in mind” for all students by the end of Grade 12:

Anchor Standard 1: Prepare for and participate effectively in a range of conversations and collaborations with diverse partners, building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively (CCSS, 2010).

The skills leading to this anchor standard progress from grades K-12 and highlight the importance of engaging students in high-level collaborative conversations in which critical thinking around text or information take place—in other words, academic conversations.

Academic conversations are intentionally structured and focus on giving students the structure and language to actively talk about their own learning and thinking process. Depending upon the targets for the conversation, students may need to summarize events or make specific references to cause and effect. They might need to argue a particular position and support that position with specific evidence.

Among their many benefits, academic conversation skills can promote higher-order thinking through the active engagement between student schema and new knowledge. This ultimately increases learner confidence and independence. Additionally, engaging students in academic conversations is a means to provide responsive academic language instruction, especially when there are intentional strategies used to help students bridge from their home language to the language of school (Hollie, Davis, & Andrew, 2015).

Gathering evidence from academic conversations

Academic conversations provide an opportunity for students to activate and integrate their knowledge as they engage in dialogue around specific concepts. Yet, to gather authentic evidence and effectively identify concepts, gaps, or even misconceptions in student understandings, educators need to be intentional about how they are structured and managed. Here are some considerations for effectively structuring and gathering evidence during academic conversations:

Be clear about what you are looking for. What specific learning target are you observing during the conversation? For example, are students being asked to support their ideas and opinions about a particular topic with examples from the text? Are they being asked to synthesize or summarize what they hear their conversation partner share? Your focus should be clear and strategic based on essential learnings that are priorities for student learning. Also, by prioritizing the focus, gathering evidence during conversations becomes more manageable.

Ensure your prompts are aligned to the targets and will engage students in high-level cognitive and communication skills. For example, you might ask students to engage in conversation about a particular character by asking them to share what the character showed the reader about the influence of key events and how the character responded because of his/her nature. This prompt goes beyond restating facts (DOK 1). The prompt challenges students to communicate their analysis of what they’ve heard or read (DOK 3). In science, students may be asked to share their models to their conversation partners and explain the phenomenon they observed during their investigations, supporting not only with observations but identifying any patterns they notice. Both examples stretch students to use critical thinking and integrate skills of effective communication very specifically in a collaborative context.

Establish expectations for quality with students. Working in collaboration with others teaching the same grade level or course, you may establish a common rubric for the skills you are looking for during academic conversations. As with any good practice, once we have a clear picture of what we are seeking, we want to make the targets clear for students. They need to understand not only the skill that is targeted during the conversation but also the picture of quality for that skill. Students can also be engaged with clarifying the expectations by codeveloping the rubric.

Have a game plan to gather evidence

Be intentional to ensure that you’re observing each student over a period of sessions. Educators can use Google forms such as the one provided below or other recording devices as they walk around the room.

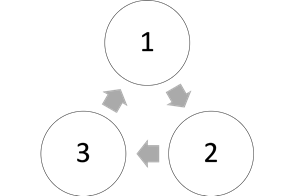

For instance, you may observe students sitting in a certain section one day, or select 7 students to observe on a rotating basis across the week. Upper elementary and secondary students can also be taught to gather evidence by having them observe a pair of students and “assessing” whether a particular skill is demonstrated. For example, students can be arranged in trios during their conversation (see below). In this arrangement, the conversation session would be divided into three 10-minute segments. During the first 10 minutes, Students 1 and 2 would talk while student 3 checks student 1 using the observation checklist. This process would continue during the next segment, with Students 2 and 3 talking while Student 1 checks 2, and then during the final segment, 1 and 3 talk while 2 checks 3 (Irwin, 2016).

Provide students “bridges” that empower them to participate in high-level conversations. Providing supportive protocols and scaffolds for students empowers them to bridge their language and/or cultural structures into academic conversations. Some students may require models, graphic organizers, sentence frames, “jumping in” strategies, or other prompts that empower them to engage at higher levels of discourse. Without them, students may struggle and avoid engagement in similar conversations. Remember, the goal is to build confident and independent learners, so the ultimate goal is to fade student dependence on the supports over time.

Ensure that students give and get timely feedback leading to improved performance. Many students come to school with cultural or language backgrounds that don’t transfer automatically to academic conversations. As part of a learning partnership in a culturally responsive classroom, teachers should work from the stance of what Zaretta Hammond (2015) calls a “warm demander.” Within this learning partnership, trust is key. Evidence from observations can be shared with students in a non-threatening manner and together, new strategies can be identified to help students grow in their confidence and skills. When these are done with a partnership mindset, students can take greater ownership and experience a sense of self-efficacy.

Engaging students in academic conversations has been identified as a powerful strategy for enhancing critical thinking and strengthening language connections. As such, it offers educators a window into students’ depth of understanding and their ability to communicate using academic language and conversational structures. When educators capitalize on the power of academic conversations, they can provide feedback to students, activating a continuous improvement cycle and increasing the likelihood that students will further develop these skills.

Hammond, Z. (2015). Culturally responsive teaching and the brain: Promoting authentic engagement and rigor among culturally and linguistically diverse students. Corwin, a SAGE company.

Hollie, S., Davis, A., & Andrew, E. (2015). Strategies for culturally and linguistically responsive teaching and learning. Shell Education.

Irwin, D., (2016). Navigating a sea of words: An assessment of academic conversation. Accessed at http://exclusive.multibriefs.com/content/navigating-a-sea-of-words-an-assessment-of-academic-conversation/education

Zwiers, J., & Crawford, M. (2011). Academic conversations: Classroom talk that fosters critical thinking and content understandings. Stenhouse.